An Overview of Go

Go is a game of territory. Go is an Asian board game where players can create an incredibly sophisticated strategy, much like chess is to the West. Go has a significant historical and cultural meaning in Japan. Go is a board game of strategy created in China thousands of years ago. Despite straightforward rules, this game’s complexity is such that mastering it has long been regarded as an art form, much like painting, music, and calligraphy.

One of the three nations where the game of Go has been studied and has played a significant role in each nation’s history is Japan, China, and Korea. Two players battle in the board game to control the most essential part of the playing board. Go was a game played by the Samurai to understand military tactics, and eventually, professional Go leagues emerged. Players who have dedicated their lives to studying the game of Go compete for titles in competitions held in castles or temples.

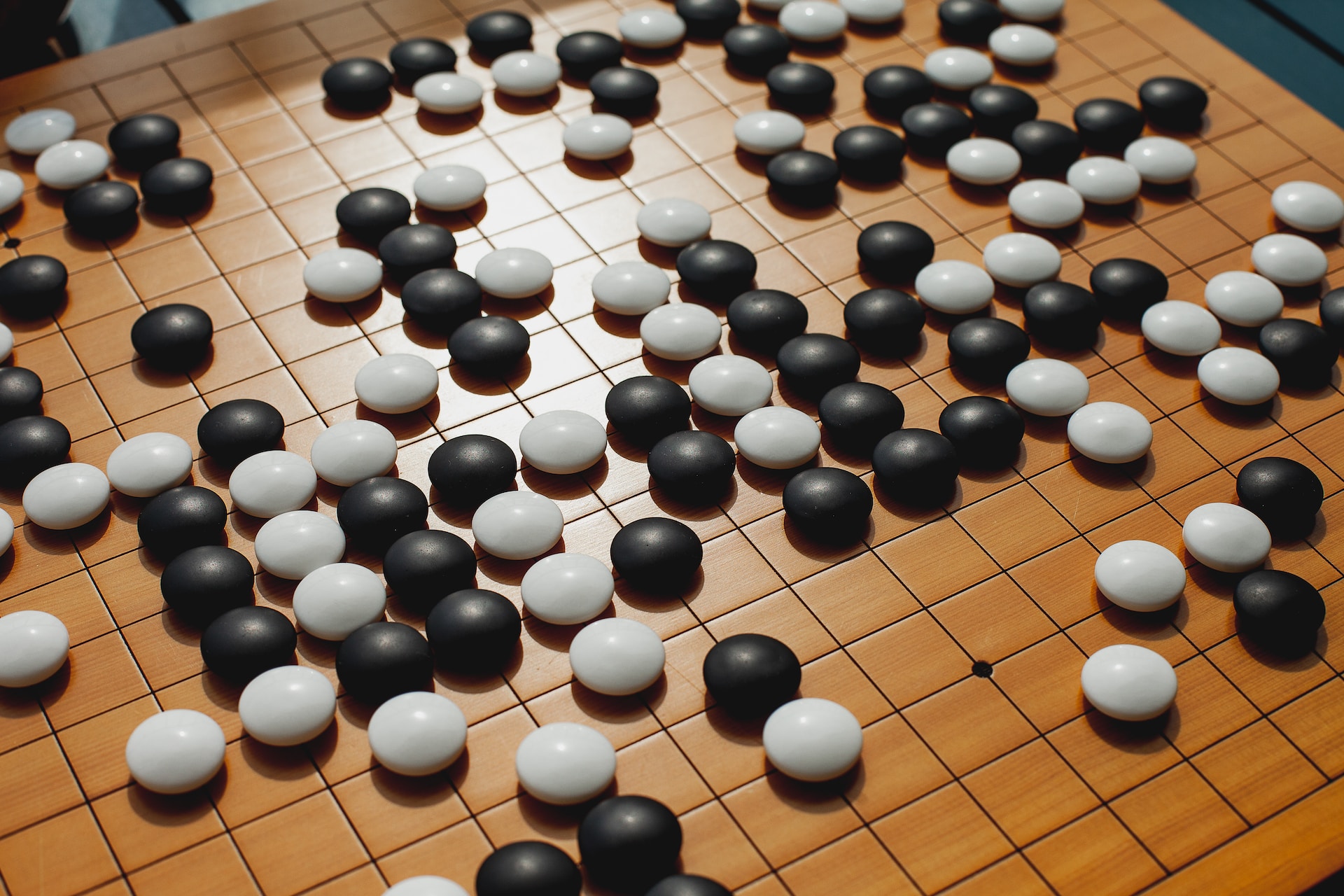

Go is a skill-based game like chess; it has been compared to four Chess games playing simultaneously on one board, yet, Go is different from chess in many respects. Go has relatively simple rules, and while the game tests players’ intellectual ability, like chess, there is much more room for intuition. A 19 by 19 board and several black and white stones are typically used in the game of Go. Go has endured the test of time because it is simple to learn and challenging to master. For anyone, learning how to play Go can be a gratifying experience. Games that are simple to understand are excellent for teaching to friends and family since they can be picked up fast and enjoyed by individuals of all ages. This game also has a lot of strategic complexity, so you can constantly improve.

The History of Go

Go is one of the oldest board games in the world; Go is so intricate that it has more moves than atoms in the known universe. Though its true ancestry is uncertain, its development is widely recorded, and although it probably indeed started in China between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago, there are also recorded theories where Go was also visible in several historical accounts of other countries. Go has history is almost as intricate as the game itself, spanning from the ancient Chinese courts to Korea, Japan, and later Germany and the rest of the world. There are several stories regarding the game’s beginnings because there aren’t any facts available, such as the one that claims the legendary Emperor Yao created Go to educate his son Dan Zhu.

The 4th century BCE historical annal Zuo Zhuan contains the oldest extant mention of the game of Go, which was then known as Yi. However, it is believed that the game originated far earlier than that. The mythological Emperor Yao (2356-2255 BCE), who allegedly ordered his counselor to make the game for Yao’s high-spirited son, is credited with creating it, according to many stories. According to some origin myths, the game was developed as a tactical tool for warlords who wanted to plan their operations. Go is credited in some traditions as an early kind of divination.

Regardless of its beginnings, Go had already become well-known when Confucius and Mencius wrote about it. It was regarded as one of the four cultivated arts, alongside calligraphy, painting, and playing the guqin, and it became connected with the aristocratic classes. The Sui dynasty (581-618) produced the earliest grid with these parameters. The game aims to encircle an opponent’s stones and surround the greater region on the board. Still, Go’s rules and structure were standardized when introduced to Korea and Japan.

The Story of Go in Japan

Historically speaking, the game indeed took off in Japan. Go was undoubtedly introduced to Japan well before the eighth century. It quickly became popular at the Imperial Court, and from this promising beginning, it became rooted in Japanese culture. The top four Go players received stipends from the Shogun in 1612. Later, the stipends were extended to the players’ successors, establishing the four illustrious Go schools: Honinbo, Hayashi, Inoue, and Yasue.

The intense competition between these schools over the subsequent 250 years significantly raised the level of play. Professional players were divided into nine grades, or dans, with Meijin, which means “expert,” being the highest grade. Only one individual could hold this title and be given to a player who outperformed his contemporaries.

The Meijin Dosaku, the fourth leader of the Honinbo School and arguably the greatest Go player in history, made the most important contributions to go theory in the 1670s. Of the four Go Schools, The House of Honinbo was by far the most productive in creating more Meijins than the other three schools combined. When the Shogunate fell, and the Emperor was reinstated in power in 1868, the foundation of professional Go in Japan was destroyed.

As Japanese culture became more Westernized, the Go colleges lost their funding. Honinbo Shusai handed over his title to the Nihon Kiin, the premier organization for professional go players in Japan, upon his retirement in 1938, so it might be given in a yearly competition among the best players. Since then, several significant competitions have been added, with the Meijin and Kisei tournaments being the most important. Go has recently seen considerable popularity in Japan, especially among young people, thanks to the immensely famous animation Hikaru no Go. There are roughly 500 professionals out of the estimated 10 million Go players in Japan. The Nihon Kiin now promotes the game’s global appeal in an expanding manner.

The Reign of Go in China

Wei Qi, which translates to “surrounding game,” is the name given to go in its native China. By the time Confucius lived, it was already one of the “Four Accomplishments” that Chinese gentlemen were required to master. Go professional players, who outlined the game’s heritage as another highbrow artistic discipline. Go was primarily a game played by intellectuals in ancient China, notably those from the affluent and the bureaucracy. This game is so tricky that only individuals with some knowledge can play it. It demands a lot of math and has excessive play variations. Later, it evolved more slowly than in Japan, and the game suffered under the Cultural Revolution since it was seen as an intellectual activity. The average person would hardly ever enjoy this game. However, because of government initiatives to popularize this ancient game, presently, Go is played by individuals from all walks of life.

Famous poet Du Mu in the ninth century once penned a poem about playing with his companion a game of using a catalpa table and jade stones to play a final round of Go. The Yunzi, pebble stones from the region of Southwest Yunnan, are the most popular stones used in the game of Go. Numerous literary works, many of which have a scene or two with the Go board, make clear the impact of the game of Go on Chinese society. In “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” a Chinese classic, the illustrious commander Guan Yu is shown playing Go while having surgery on his arm. Another commander, Fei Wei, organized his unit deployments visually using a go board. According to history books, each dynasty produced many passionate Go enthusiasts, including emperors, bureaucrats, poets, educated ladies, and even monks.

The Chinese players have once more caught up to the Japanese since the professional system was established in 1978. Wei Qi is now taught at numerous schools, and competitions are held nationwide. There is also the yearly game between China and Japan, attracting much attention. China now has several elite athletes, such as Ma Xiaochun and Chang Hao, who have excelled in international competitions. Meanwhile, the number of Go enthusiasts in China is currently 36 million and growing thanks to extensive media coverage. Some universities, like Beijing University, offer undergraduates evening courses in Go. More kids are enrolling in private Go lessons as Wu Yulin trains his squad of young players to advance in the game of Go. Only time will tell which will emerge as tomorrow’s brightest stars.

Go to Korea- Baduk

Traditionally played in Korea, the game of go was much different from that of China. Although it originated in the late 16th century, its origins may be similar to how Go was first played. The traditional Korean Go game slowly vanished; however, in 1937, it saw the final known game before it disappeared because of the rediscovery of Yi Seung-u (Lee Sungwoo), a Go writer. The term “old Korean go” (sun-chang pa-tuk, Xinjiang back) describes the game. The game was played on a traditionally marked board with 17 starting-stone markers; there are still some examples of these boards. Each player set Eight stones on the points, and Black then started the game.

Go, commonly referred to as Baduk in most households in Korea, is incredibly well-liked. Koreans are known for playing quickly. Whether quick or not, they create some of the most influential athletes. When Cho Nam-Chul returned from professional training in Japan in the 1950s, their professional system had already been established. Baduk is currently more well-liked in Korea than everywhere else on Earth. Between 5 and 10 percent of the population are thought to play routinely. There are numerous newspaper-sponsored events with sizable and committed audiences, just like in Japan. Some of the best Korean athletes have recently won spectacular international competitions. There is little doubt that Korea is home to some of the best athletes in the world today.

Go Invasion in Europe and Britain

Even though Westerners who traveled to the Far East in the 17th century described the game of Go, it was when German author Oskar Korschelt published a book about the game in 1880 that it was played in Europe. Following this, some Go was played in Yugoslavia and Germany. The first regular European Championship did not occur until 1957 since the sport took a while to catch on. Today, go is played in most European nations. The level of play is substantially lower than that of the best players in the Far East, although the difference is gradually closing as more of the best European players travel to Japan, Korea, and China to study the game. Some continue in their careers.

A fantastic record was set on May 21st, 2016, in St. Petersburg when more than 200 people played Go in the city’s heart. On this day, 27 of the top Go players in the nation competed against 191 other players in simultaneous games. As a result, the game grew to be the biggest Go game in Russian history. Different players, including renowned pros and amateurs and young and old Go enthusiasts, participated in these simultaneous games. There were also new visitors, individuals who had never heard of the game before, and they got to learn the rules and play the game.

Meanwhile, Go has been played in Britain for at least 100 years. Still, the British Go Association was established in the 1950s, when organized play began. There are currently about 100 Go clubs in Britain, and the level of play is comparable to that of the rest of Europe. Britain’s top player in recent years, Matthew Macfadyen, has won the European Championship four times. Every year, there are no competitions across the country nor the British Championships and British Youth Championship. These frequently draw 100 players, many newcomers, and young players. Since 1968, an open British Go Congress has been held annually at a new location. The London Open is one of the leading competitions on the Toyota-Pandanet Tour, which spans Europe.

The Things You Need to Know to Play Go

Go is a game played by millions of people worldwide. It has grown in popularity due to its straightforward rules and intricate strategy. Learning the fundamentals of how to play this engaging game is a pleasant experience that can be enjoyed by players of all ages and ability levels, even though mastering the nuances of Go may take years of effort. The basic principles of Go will be covered in this article, giving you a firm basis for starting your Go-playing experience.

1. The Go Game Equipment

You will need A goban, a Go board, black and white stones, and bowls to keep the stones required for the game of Go. Depending on the nation, these games’ styles can vary.

The Goban board

A hardwood board with a grid of 361 intersections is called a “Go board,” or “goban” in Japanese. In Japan, the goban was a plain board and a little table with legs that the players sat in front of on tatami mats. Go, boards today are made to be used on a standard table. The goban appears to be a clear wooden cube, yet it is a particular piece of artwork. The Go board is made from a single piece of wood and is roughly 15 to 20 cm thick. The type of wood and the area of the tree from which it is made determine the goban’s quality.

Go boards, are often made of kaya, a coniferous tree that only grows in Japan and Korea. As a result, the kaya goban is very pricey. A perfect cut go board made of kaya wood can be purchased for over 20,000 dollars! Of course, you can find gorgeous Go boards for far less money. Go boards made of shin-kaya, or “new kaya” in Japanese, which is spruce, are probably the most well-known, although there is also goban made of oak, beech, and bamboo.

The Go Stones

Black and white stones, or geisha () in Japanese, are necessary for the game of Go. Slate and shell are the materials used to create the stones in a conventional game of go. One of the most expensive components of a Go game set is the white stones made of shell. Since each stone is polished by hand, it is true craftsmanship. It is a type of traditional craftsmanship that was first created in Hyuga City, Miyazaki Prefecture, on the island of Kyushu. The shells used to produce Go stones were initially widely available on the Hyuga beaches. Although the shells now come from Mexico, Hyuga’s artisans continue to produce most Japanese go stones because of their unique expertise. Each shell stone has a distinctive grain pattern. The stones exhibit the natural beauty of Japan in a very straightforward manner. There are 361 stones in a game of Go: 181 black stones and 180 white stones. Each stone is individually created; therefore, it takes a lot of labor. Stones are divided into various groups based on the stripes’ width and density.

The Bowls of Go

The stones are kept in the bowls, and the captured stones are set down on the lid during play. The bowls might not appear as necessary as the stones or the Go board. Still, they are an integral component of the overall visual experience of a game of Go created by Japanese artisans. The bowls are made from a variety of woods. Since each bowl is handmade from a single piece of wood, it is unique and has a distinctive pattern. The expensive bowls are constructed of black persimmon wood (), which gives them very distinct and contrasty designs, or mulberry wood from Mikura-Jima, a tiny island south of Tokyo.

2. The Objective of Go

A blank board is used to begin a game of Go. The number of pieces or stones available to each player is practically unlimited; one player takes the black stones, the other the White. The game’s primary goal is to surround empty spaces on the board with your stones to create territories. The opponent’s stones can also be taken by completely encircling them. By capturing your opponent’s stones, you can achieve this. All the stones of the same color are given to each player, and they are placed one at a time to construct chains and obstruct the moves of the other players.

3. Placing of Stones

Stones are placed on any open intersection of lines by players in turn, one at a time. Players are not allowed to change their minds or move a stone once it has been put. In general, it is a good idea to lay your stones close to other stones you have already set. As long as there are nearby vacant points known as “liberties” connected to the spot in question, stones may be put on any open point of intersection between the lines on the board. Remember that only the cardinal directions count in the game of Go.

4. Capturing Stones and Counting Liberties

A stone is considered to have been captured when surrounded by opponent pieces and is worth one point. Liberties are empty locations that are horizontally and vertically next to a stone or a string of firmly attached stones. When all the liberties of an independent stone or a string of connected stones are occupied by enemy stones, the stone is taken. Compared to stones in the middle of the board, stones on the edge of the board have fewer liberties. There are three liberties for a single stone on the side but only two for a stone in the corner.

5. Capturing Strings

A group of stones is one unit to capture. A string is taken when all its liberties are occupied by hostile stones, as with lone stones. A player is not allowed to self-capture, which is to play a stone into a position where it would have no liberties or build a string without liberties unless one or more of the stones around it are also captured.

6. The Live and Dead String

A “live string” or “live group” is any string of stones with two or more eyes, which makes them permanently impervious to capture. In contrast, a string of stones incapable of forming two eyes, severed and encircled by living enemy threads, is referred to as a dead string because it is helpless and unable to resist being captured. In a real game, after it is obvious to both players that the string is dead, neither player is required to finish the capture of an isolated dead string.

7. The Ko Rule

The ko rule, derived from the Japanese word for forever, prohibits players from continually capturing and recapturing the same single stone pieces, which would halt the game from moving forward. The ko rule dictates that after being taken, a player must hold off on recapturing for at least one turn, even if they can do so immediately. The Ko rule only applies to single-stone catches, so remember.

8. Seki – Go Stalemate

Typically, a string that cannot produce two eyes will perish unless one of the enemy threads in its immediate vicinity is likewise blind. This frequently results in a race to capture. Still, it can also lead to a stand-off condition known as Seki, where neither string has two eyes but cannot capture the other due to a lack of liberties.

9. Scoring and Claiming territory

Claiming that territory includes enclosing a point of intersection or even a collection of points. However, either player may continue to set stones inside that claimed region to try and claim some of the points if there are points with open liberties there. One point is awarded for every junction in a territory that is claimed and for every enemy stone that is taken. The open point left by a captured piece will also score as a point for the player who captured it since, as previously said, stones are removed from the game board once caught.

10. The Handicap System

The handicap system in the game of Go is one of its best aspects, as was said in the introduction. A player who is weaker than them may receive a benefit of up to nine stones. These are put on the board instead of Black taking the first turn. White can now play after all the handicap stones have been set in place. The grading method makes it simple for any two players to determine how strong they are different from one another and, consequently, how many stones the weaker player should take to make up for this discrepancy. Since a player’s grade is expressed in stones, the handicap’s number of stones equals the grade gap between the two players.

11. The Komi

Playing first benefits Black naturally more than White. Therefore, in games involving players of equal strength, it is customary to increase White’s score to compensate for the disadvantage of playing second. These are referred to as Komi. This is the typical size of the Komi because, in our experience, playing first is worth around 7 points. To prevent ties, Komi is frequently set at 7.5 points during competitions. Black is the weaker player in a one-stone handicap, while White is not granted Komi.

12. The Ending of the Game

You pass and surrender a stone to your opponent as a prisoner when you believe all your territories are secure; you can no longer expand your territory, shrink your opponent’s area, or capture more strings. The game is over after two passes in a row. Any strings with no chance of success are cut and taken prisoner. Continue playing if you cannot agree whether a string is dead or alive; you can then finish capturing disputed strings or determine they are active. Since each play is the same as a pass, playing during a continuation does not affect the score. Since Black played first, White must play last and could need to make another pass.

Tips for Winning Go

Go tends to reward perseverance and pattern recognition, in contrast to games like chess, which are more logic-focused. Being one step ahead of your opponent requires understanding how they usually play the game.

1. Keep Track of Liberties

One of Go’s most crucial, fundamental skills is keeping track of liberties or the number of unoccupied spaces that touch any point or stone on the board. The secret to success is to limit your opponent’s freedoms while enhancing your own. For this reason, it’s critical to remember that bent lines will always have fewer liberties than straight lines when compared point for point. This means a bent line is less complicated for your adversary to encircle and subsequently claim than its straight counterpart.

2. Protect Your Stones

For novice players, safeguarding your stones is a Go principle that is frequently disregarded. Capturing additional space requires finding quick maneuvers to prevent the opponent from capturing your stones in the future.

3. Acquire Territories

Players can occasionally become too preoccupied with seizing enemy stones to remember the game’s primary goal. Early on, you can assist in controlling more of the board and make it challenging for the adversary to regain control by circling unoccupied sections of the board with your pieces.

4. Assess the Whole Board

Consider whether it would be wiser to respond to your opponent’s move or to place a stone in a different location when they place a stone. Always consider the entire board before deciding. There may be a chance someplace. You will lose the game if you constantly pursue your adversary. This is a standard error made by newbies.

5. Play where there is more space.

In Go, playing in expansive, open spaces is best. The board’s corners are the most significant regions, followed by the sides and the middle. The least number of movements are needed to encircle corners and sides.

6. Watch out for the Eye

In Go, claiming territory your opponent cannot retake is best because doing otherwise would be against the rules. In Go, these secure, impregnable clusters are called “eyes.” A region is referred to as having a “false eye” if it initially seems safe but can be recovered by your opponent. Players frequently miss these weaknesses until it is too late. It is naturally simpler for your adversary to capture or recapture a group with only one gap than for a shape with two eyes. Consequently, a group with only one Eye is practically dead.

7. Try to stay away from edges and corners.

The edges of the board become exposed as stones are placed there. They have fewer liberties than stones placed in open spaces because one or more sides are already sealed. If using the edges gives you a significant advantage, only do so.

8. Watch Your Back and Front

Always strive to keep an eye on what your opponent is doing or attempting to do while executing your game plan. You must enter his mind to understand his strategy. Your ability to prepare yourself and play with more composure will increase as you become more aware of his goals. Also, remember that trying to oppose everything is only sometimes a good idea. Cooperation is sometimes the best course of action. Every person has a different capacity for seeing the various possibilities on the Go board, depending on their skill level and experience. To get better at the game, it helps to picture the board’s several moves in the future. To defeat more powerful opponents, developing your ability to visualize the board several moves in advance is critical.

9. Be Familiar with the Shapes of Life and Death

A few fundamental forms frequently come to mind when thinking about the various ways that clusters of stones might form liberties and eyes. The “shapes of life and death” are what they are called, and as their dramatic name suggests, understanding the shapes might be the difference between winning and losing. The number of points in the Eye and the shape the points are in, respectively, can be used to categorize all forms of life and death. A straight two, or two points in a row, is a dead form. A straight two can be surrounded and captured regardless of how the two free points are split since it is too small to be divided into two eyes.

When you have three points or more in a group, turn order matters a lot more in determining whether a group survives. The phrase “sente lives, gote dies” refers to the belief that the player who makes the play first will ultimately win the game. Such shapes include the straight and bent three, where the first player to place a stone on the middle spot will either rescue the group or destroy it. A “vital point” is the term used to describe this crucial location. Like sente lives, gote dies, a group of four in the shape of a T, sometimes known as a pyramid four, is also used.

Since the crucial location is in the middle, whoever places a stone there will kill or save the group. The straight four and the bent four, which resemble an L, are considered safe “alive” groupings since they have more than one crucial point. They can no longer be captured because two eyes will still be produced no matter which space is played on first. On the other hand, a group of four points arranged in a square is a dead one.

The crossed five, also known as the flower five or the five with a critical point directly in the center, is a sense of life, gote dies shape. Similarly, a “knife handle” or “bulky” five has four points in a square with a fifth point protruding. The point that isolates the fifth point, often known as the knife handle, leaving a bent three, is crucial for this design. The rectangular six, or six points in a rectangle, is an “alive” shape like the bent and straight fours. On the other side, the “rabbity” six is sente survives; gote dies, with a crucial point in the center. The two extra points protruding from a group of four in this shape are like the ears of the rabbit.

10. Study and practice the game.

To think more strategically than your opponent in the game of Go, you must first learn to notice shifting liberties, shifting eyes, and the shapes of life and death. Like chess moves, the shapes are reference points for more experienced players. To improve your Go skills, you should start studying. Making a clever trap or getting caught in one frequently depends on being one step ahead of your opponent.

Conclusion

Go has been played for three to four thousand years, and during that time, the rules have practically stayed the same. The game most likely originated in China and Japan. Go is still quite popular in the Far East, where it first appeared, and interest in the game is rapidly rising in Europe and America. Go is a skill-based game like chess; it has been compared to four Chess games playing simultaneously on one board, yet, Go is different from chess in many respects.

Each player takes a turn, placing a stone on an open location on the board as the game begins. The stones are positioned at the intersections of the lines rather than in the squares when Black plays first. Stones are not shifted after being played. They might, however, come under attack and be captured; in that event, they are taken off the board as prisoners. The players typically begin the game by laying claim to areas of the board that they plan to surround and turn into territory eventually. Players score one point for each open intersection inside their region after the game and one point for each stone they have taken; the one with a higher score wins.

Gaining territory through the capture of stones is unquestionably one of its complexities, but aggression isn’t always advantageous. The game’s limitless strategic and tactical options provide players of all skill levels with challenge and fun. On the Go board, the players’ characteristics stand out sharply. The game displays the abilities of the players in balancing attack and defense, making stones operate well, maintaining adaptability in the face of shifting circumstances, timing, precisely analyzing, and identifying the advantages and disadvantages of the opposition. Go is a game that you cannot outgrow, to put it simply.